ABOUT DUGONGS

(this Page is being continuously updated)

Dugong facts

Dugong mother and baby taking a breath.

Dugong mother and baby taking a breath.

s• IUCN classification = "Vulnerable to Extinction" and locally extinct in the Province of China, Mauritius, Taiwan; nearly extinct in Mozambique, Vanuatu, with relict populations in south Pacific islands.

• The Queensland government's Nature Conservation Wildlife Regulation lists dugongs as "vulnerable to extinction."

• The New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 lists dugongs as "Endangered."

• The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, which Australia signed and ratified) lists dugongs as "Endangered" and bans the trade of these animals worldwide.

• Life span (maximum longevity - most dugongs die at a younger age) = 70 years

• Age before breeding (females) = 10-16 years

• Age before breeding (males) = 10-17 years

• Gestation period = 13-15 months

• Number of babies per pregnancy = 1

• Lactation length = 16-18 months

• Time between pregnancies = 3-7 years

• Juvenile mortality (not including hunting): 10-30%

• Adult mortality (not including hunting): 2-4%

• Maximum possible rate of increase in population (e.g. low natural mortality and no human-induced mortality) = 5%

• Estimated natural mortality rate (not including hunting, boat strikes and illegal gill nets) = 5%. This means that if human causes of dugong deaths were eliminated, the population would be stable. Since thousands of dugongs are killed every year due to hunting, ship strikes, and pollution, their population is steadily and severely declining.

Information based on the Australian Government's Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and R. Heinsohn et al, "Unsustainable harvest of dugongs in Torres Strait and Cape York (Australia) waters: two case studies using population viability analysis" Journal: Animal Conservation, volume 7 (issue 4, 2004): pp. 417-425.

• The Queensland government's Nature Conservation Wildlife Regulation lists dugongs as "vulnerable to extinction."

• The New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 lists dugongs as "Endangered."

• The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, which Australia signed and ratified) lists dugongs as "Endangered" and bans the trade of these animals worldwide.

• Life span (maximum longevity - most dugongs die at a younger age) = 70 years

• Age before breeding (females) = 10-16 years

• Age before breeding (males) = 10-17 years

• Gestation period = 13-15 months

• Number of babies per pregnancy = 1

• Lactation length = 16-18 months

• Time between pregnancies = 3-7 years

• Juvenile mortality (not including hunting): 10-30%

• Adult mortality (not including hunting): 2-4%

• Maximum possible rate of increase in population (e.g. low natural mortality and no human-induced mortality) = 5%

• Estimated natural mortality rate (not including hunting, boat strikes and illegal gill nets) = 5%. This means that if human causes of dugong deaths were eliminated, the population would be stable. Since thousands of dugongs are killed every year due to hunting, ship strikes, and pollution, their population is steadily and severely declining.

Information based on the Australian Government's Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and R. Heinsohn et al, "Unsustainable harvest of dugongs in Torres Strait and Cape York (Australia) waters: two case studies using population viability analysis" Journal: Animal Conservation, volume 7 (issue 4, 2004): pp. 417-425.

human causes of dugong deaths

PESTICIDES KILLING SEA GRASS, DUGONGS' ONLY FOOD

Worldwide conservation organizations (e.g. SeagrassWatch) report that seagrass meadows are declining everywhere due to the pesticides contained in water runoff from industrialized farming. The decline of seagrass is a critical threat for dugongs. When dugongs cannot find grazing grounds and become malnourished, they slow down or even stop reproducing. Their reproductive cycle is already very slow, taking 6 years or more for an adult female to produce a single calf. When seagrass is not available, this interval can be substantially longer. Additionally, dugong calves are particularly vulnerable when seagrass is not available; malnourishment increases their mortality at a young age, while also depriving nursing dugong mothers of their milk.

HUNTING

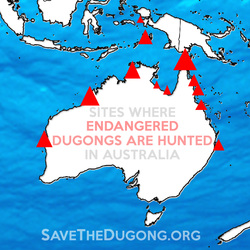

Australian law still allows the hunting of endangered dugongs and other endangered species that live only in this country. Australia is the only developed country that allows legalized hunting of this endangered species. Click here for a full map of dugong hunting sites worldwide. Due to the cost of food and impoverished conditions in many communities in Australia's northern regions—whose waters dugongs inhabit— many communities resort to hunting dugongs as a source of food, or even selling their meat to foreign markets (prohibited by law), in order to survive. Government policies have failed to address this problem and provide a meaningful alternative, e.g. reducing the rising price of food in remote areas, or offering alternatives for income, such as sustainable tourism development.

According to the Dugong and Marine Turtle Knowledge Handbook, published by Northern Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance, dugong hunting practices include:

Australian law still allows the hunting of endangered dugongs and other endangered species that live only in this country. Australia is the only developed country that allows legalized hunting of this endangered species. Click here for a full map of dugong hunting sites worldwide. Due to the cost of food and impoverished conditions in many communities in Australia's northern regions—whose waters dugongs inhabit— many communities resort to hunting dugongs as a source of food, or even selling their meat to foreign markets (prohibited by law), in order to survive. Government policies have failed to address this problem and provide a meaningful alternative, e.g. reducing the rising price of food in remote areas, or offering alternatives for income, such as sustainable tourism development.

According to the Dugong and Marine Turtle Knowledge Handbook, published by Northern Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance, dugong hunting practices include:

1) Chasing a dugong for up to several hours, until the animal is completely exhausted and needs to pause on the surface to breathe.

2) Spearing the animal with multiple metal tips (usually made of nails), tied to ropes, in order to subdue the dugong and reel it closer to the boat.

3) Grasping the dugong by the tail in order to submerge its face underwater, causing it to drown. This process can take up to 20 minutes. During this time, the dugong struggles and thrashes, trying to reach the surface to breathe.

4) Tying the live dugong to the hunters' boat by the tail and dragging it to shore, while the head is submerged underwater, eventually drowning the animal, a process that can take several hours. This is almost always done with modern vessels, which are not among the traditional tools allowed for hunting.

5) If attempts at drowning the animal fail, the dugong is dragged to shore alive and butchered, or killed by hurling rocks at its head.

6) There have been documented cases of dugongs butchered alive on shore; ABC7.30 News has aired video footage of endangered green sea turtles killed the same way.

7) Hunters prefer targeting pregnant females, due to the fattier meat they provide.

8) Hunters have been documented (with photographic evidence) to cut the unborn dugong fetus out of pregnant mothers.

8) Hunters have been documented (with photographic evidence) to cut the unborn dugong fetus out of pregnant mothers.

9) Hunters also routinely catch young dugong calves (NTNews story here including hunter testimony), even when still nursing, in order to attract the mother, who will desperately chase the hunters' boat for hours, all the way to shore. Hunters then spear and/or catch the mother, and butcher both mother and calf, or release the calf to die of starvation alone in the ocean.

10) Photographic evidence shows that multiple dugongs and turtles are caught in each hunting trip, far exceeding the personal needs of hunters as prescribed by Native Title Act 1993 (section 211).

A sample video of the whole hunting process (not produced or in any way connected to this site) is available here.

A sample video of the whole hunting process (not produced or in any way connected to this site) is available here.

BOAT STRIKES

Data relative to dugong deaths due to boat strikes is maintained only by the Queensland Environmental Protection Agency (page 21). According to their figures, 8 stranded dugongs have been documented as victims of boat strikes in Queensland between 1996 and 2011. The data is obviously incomplete. Even so, the same government survey show that hunting is responsible for several thousands of dugongs being killed every year. Based on the available data, it is clear that the primary threat to the dugong population is hunting.

Data relative to dugong deaths due to boat strikes is maintained only by the Queensland Environmental Protection Agency (page 21). According to their figures, 8 stranded dugongs have been documented as victims of boat strikes in Queensland between 1996 and 2011. The data is obviously incomplete. Even so, the same government survey show that hunting is responsible for several thousands of dugongs being killed every year. Based on the available data, it is clear that the primary threat to the dugong population is hunting.

ILLEGAL GILL NETS AND DISCARDED FISHING GEAR

What does "dugong" mean?

ORIGIN OF THE NAME "DUGONG"

• Dugong in Tagalog (a language spoken in the Philippines) means "lady of the sea." The name refers to the fact that dugongs were the inspiration for mermaid legends among sailors in the age of exploration. The shape of the dugong, as sighted from a ship, may be mistaken for the outline of a human with a dolphin tail, while (allegedly) the female dugong keeps her head above water while giving birth, emitting high pitched sounds which may have been interpreted by sailors as mermaids singing.

AUSTRALIAN TRADITIONAL INHABITANTS' TERMINOLOGY

The following terminology is referenced in the Dugong and Marine Turtle Knowledge Handbook, published by Northern Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance.

• In the Yanyuwa language, spoken by inhabitants of the Sir Edward Pellew Islands and surrounding sea country in the south-western Gulf of Carpentaria (a major dugong hunting ground), the following terminology is used for dugongs:

- waliki/nhabal - general term for all dugong

- li-waliki/&-waliki - a herd of dugong

- a-banthamu - old female dugong

- a-bayawiji - mature female dugong

- a-ngayiwunyarra/a-kulhakulhawiji - pregnant female dugong targeted because of its fat meat.

- a-lhumurrawiji - pregnant female dugong with baby following her.

- a-miramba - non-lactating female dugong with baby still following her.

- a-ngarninybala - female dugong with baby riding on her back.

- a-wuduwu - young female dugong.

- li-milkamilarra - small group of female dugongs with babies.

- nyankardu - dugong fetus.

- bungkurl - very fat male dugong

- jiyamirama/jiwarnarrila - male dugong running away from threat.

- mayili - male dugong with small tusks.

- rangkarraku/rangkarrangu - male dugong swimming alone.

- wirumantharra - male dugong whistling and leading a herd.

- ngumba - very young dugong.

• In the Yolngu language of northeast Arnhem Land the term "miyapunu" is used to refer to dugong and turtles hunted there.

• On Mabuiag Island, Torres Strait, the following terms are used to refer to dugongs:

- Garka dangal/dhangal - male dugong- Ipika dangal/dhangal - female dugong

- Kazi dangal/dhangal - young dugong

- Ngawaka dangal/dhangal - juvenile female

- Kaukuik dangal/dhangal - juvenile male

- Barakutau dangal/dhangal - juvenile male that stays with mother

- Sabi dangal/dhangal - single male

- Puru dangalal - mating dugongs

- Kazilaig - pregnant dugong

- Nanaig - nursing mother

- Gilab - large, old dugong

- Tuarlaig - herd leader

- Ulakal - herd of 5-10 dugongs

- Dangalal buai - family herd of 10 or more dugongs

- Malu dangal/dhangal - dugong swimming in a far reef

- Wati dangal/dhangal - lean dugong swimming in shallow water (considered inedible).

OTHER LANGUAGES

• In Malay, a language spoken in the South Pacific, the word for dugong is "duyung," meaning, once again, "lady of the sea."

• In Japanese, Dugong is pronounced "Jugon" (written ジュゴン or 儒良). In Okinawan, the name for dugong is "Zan" (written ザン). Japanese legends also identify the dugong with the Ningyo, a mythical mermaid inhabiting Japanese waters, likely arising from dugong sightings in Okinawa and the southern Japanese islands. According to Japanese folklore, catching a Ningyo (or dugong) brought extremely bad luck, while eating its flesh would cause extreme longevity, which in Japanese culture was seen as a curse, since a person would see all his/her loved ones die out. Okinawa is the only Japanese territory where dugongs are sighted consistently. Hunting dugongs in Okinawa is illegal and Okinawans do not eat dugong meat.

• In Palau, the word for Dugong is "Mesekiu." Dugong hunting in Palau is illegal. Tribal leaders and government authorities have teamed up to guarantee 24/7 surveillance of dugong habitats, patrolling and arresting poachers.

• In Sri Lanka, the dugong is known as "Muhudu ura," in the local Sinala language. Dugong hunting in Sri Lanka is illegal, but illegal hunting continues, while many dugongs frequently remain caught in gill nets and drown.

• In Vietnamese, the name for dugong is "Cá cúi. " Both legal and illegal hunting occur in Viet Nam, with the dugong population declining to less than a hundred.

• In Thai, the word for dugong is Phayun (written พะยูน). News reports have documented at least 25 dugongs killed every month for export to Singapore black markets, for a price of $2000 per animal.

• Dugong in Tagalog (a language spoken in the Philippines) means "lady of the sea." The name refers to the fact that dugongs were the inspiration for mermaid legends among sailors in the age of exploration. The shape of the dugong, as sighted from a ship, may be mistaken for the outline of a human with a dolphin tail, while (allegedly) the female dugong keeps her head above water while giving birth, emitting high pitched sounds which may have been interpreted by sailors as mermaids singing.

AUSTRALIAN TRADITIONAL INHABITANTS' TERMINOLOGY

The following terminology is referenced in the Dugong and Marine Turtle Knowledge Handbook, published by Northern Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance.

• In the Yanyuwa language, spoken by inhabitants of the Sir Edward Pellew Islands and surrounding sea country in the south-western Gulf of Carpentaria (a major dugong hunting ground), the following terminology is used for dugongs:

- waliki/nhabal - general term for all dugong

- li-waliki/&-waliki - a herd of dugong

- a-banthamu - old female dugong

- a-bayawiji - mature female dugong

- a-ngayiwunyarra/a-kulhakulhawiji - pregnant female dugong targeted because of its fat meat.

- a-lhumurrawiji - pregnant female dugong with baby following her.

- a-miramba - non-lactating female dugong with baby still following her.

- a-ngarninybala - female dugong with baby riding on her back.

- a-wuduwu - young female dugong.

- li-milkamilarra - small group of female dugongs with babies.

- nyankardu - dugong fetus.

- bungkurl - very fat male dugong

- jiyamirama/jiwarnarrila - male dugong running away from threat.

- mayili - male dugong with small tusks.

- rangkarraku/rangkarrangu - male dugong swimming alone.

- wirumantharra - male dugong whistling and leading a herd.

- ngumba - very young dugong.

• In the Yolngu language of northeast Arnhem Land the term "miyapunu" is used to refer to dugong and turtles hunted there.

• On Mabuiag Island, Torres Strait, the following terms are used to refer to dugongs:

- Garka dangal/dhangal - male dugong- Ipika dangal/dhangal - female dugong

- Kazi dangal/dhangal - young dugong

- Ngawaka dangal/dhangal - juvenile female

- Kaukuik dangal/dhangal - juvenile male

- Barakutau dangal/dhangal - juvenile male that stays with mother

- Sabi dangal/dhangal - single male

- Puru dangalal - mating dugongs

- Kazilaig - pregnant dugong

- Nanaig - nursing mother

- Gilab - large, old dugong

- Tuarlaig - herd leader

- Ulakal - herd of 5-10 dugongs

- Dangalal buai - family herd of 10 or more dugongs

- Malu dangal/dhangal - dugong swimming in a far reef

- Wati dangal/dhangal - lean dugong swimming in shallow water (considered inedible).

OTHER LANGUAGES

• In Malay, a language spoken in the South Pacific, the word for dugong is "duyung," meaning, once again, "lady of the sea."

• In Japanese, Dugong is pronounced "Jugon" (written ジュゴン or 儒良). In Okinawan, the name for dugong is "Zan" (written ザン). Japanese legends also identify the dugong with the Ningyo, a mythical mermaid inhabiting Japanese waters, likely arising from dugong sightings in Okinawa and the southern Japanese islands. According to Japanese folklore, catching a Ningyo (or dugong) brought extremely bad luck, while eating its flesh would cause extreme longevity, which in Japanese culture was seen as a curse, since a person would see all his/her loved ones die out. Okinawa is the only Japanese territory where dugongs are sighted consistently. Hunting dugongs in Okinawa is illegal and Okinawans do not eat dugong meat.

• In Palau, the word for Dugong is "Mesekiu." Dugong hunting in Palau is illegal. Tribal leaders and government authorities have teamed up to guarantee 24/7 surveillance of dugong habitats, patrolling and arresting poachers.

• In Sri Lanka, the dugong is known as "Muhudu ura," in the local Sinala language. Dugong hunting in Sri Lanka is illegal, but illegal hunting continues, while many dugongs frequently remain caught in gill nets and drown.

• In Vietnamese, the name for dugong is "Cá cúi. " Both legal and illegal hunting occur in Viet Nam, with the dugong population declining to less than a hundred.

• In Thai, the word for dugong is Phayun (written พะยูน). News reports have documented at least 25 dugongs killed every month for export to Singapore black markets, for a price of $2000 per animal.

History

Traditional inhabitants throughout the Indo-Pacific region have lived in symbiosis with dugongs for thousands of years. There are dugong cave paintings in Malaysia, which are dated 3000 B.C. They were discovered in Tambum cave, in Ipoh City. Extensive finds of aboriginal Australian art and artifacts from the Torres Strait show that dugongs populated these regions.

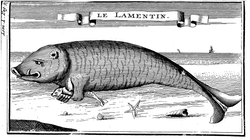

Leguat's illustration of a dugong.

Leguat's illustration of a dugong.

The first European to describe the dugong was explorer and naturalist François Leguat, in the late 17th century. In his account of his voyages in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius, Reunion islands), Leguat provided a detailed description of what he called a "Lamentin," the French word for a seacow (usually a manatee). His description of the animal's fluked tail clearly indicates that what he saw was a dugong. He described herds of as many as 300-400 at a time, mentioning the dugongs' affectionate nature. Leguat said that the dugongs would allow people to touch and pet them without swimming away, enjoying the physical contact much the same way today dugongs do in regions where they are not hunted (Leguat, Voyages, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010): pp. 75-6). Leguat also remarked upon the dugong mothers' careful parenting, affectionately holding and nursing a single calf in much the same way humans would (see illustration). Today, almost no dugongs remain in the region where Leguat observed them for the first time in such large numbers.